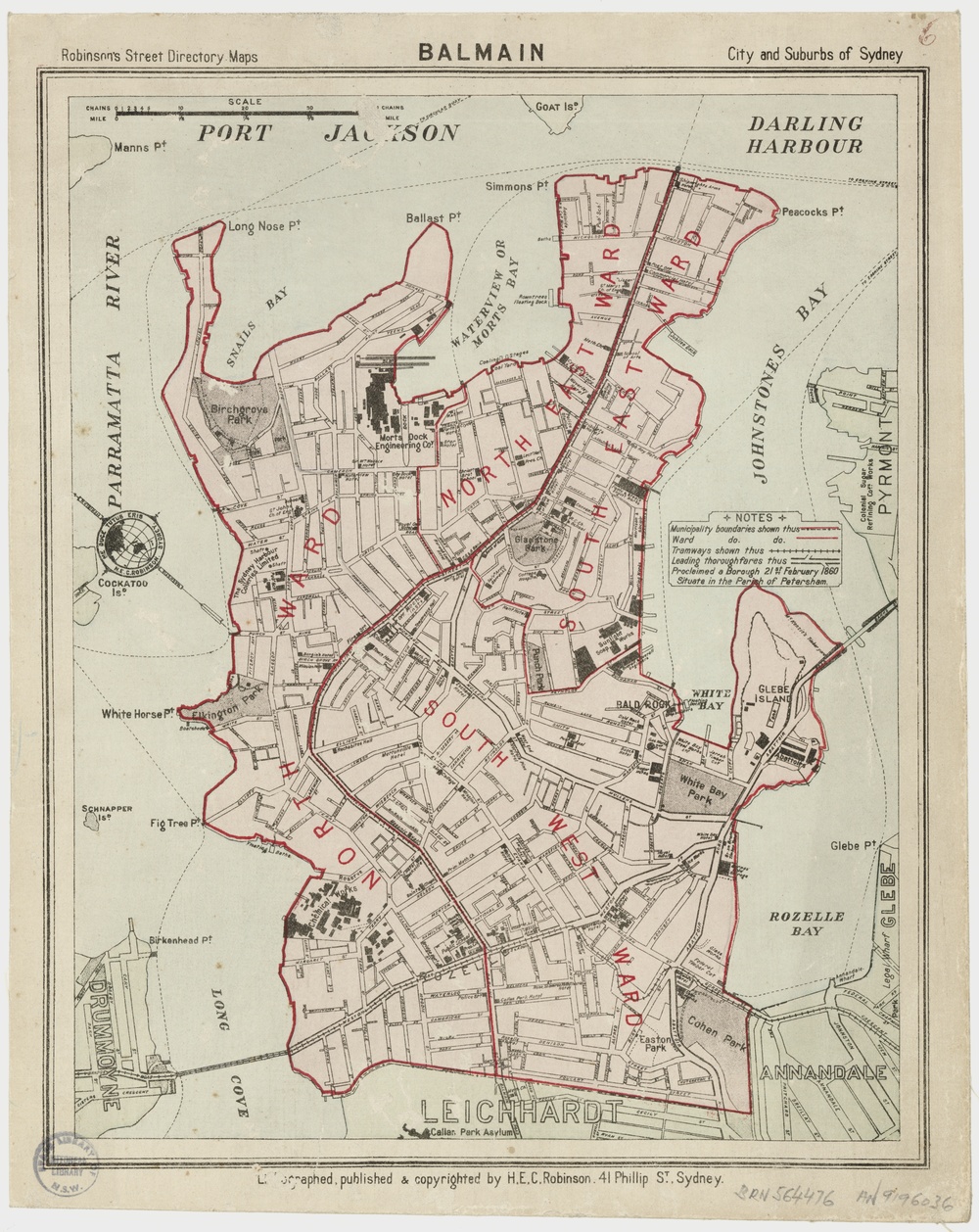

Balmain map from between 1906-1910, State Library of NSW archives, download a full resolution version here

The Balmain peninsula only lies about one kilometer west of Sydney’s “city”, separated by the natural harbour. The Wangal people have called this area their home for thousands of years before European settlement. I have walked the local streets up and down for leisure and with the baby and often wondered about the stories that have taken place here in the past.

Balmain is steeped in post-European settlement history, unlike most places down under. Helen Carter, a local writer affiliated with the Balmain Association, has put together an interesting book that recounts meticulously Balmain’s industrial history. Her Balmain Peninsula: Industrial Vandalism? draws on extended archival research and features great historical photos. Much of the content of this post leans on the book.

Balmain was one of Australia’s first industrial sites. Its origins date back to the mid-nineteenth century, when Thomas Sutcliffe Mort operated his shipbuilding and engineering firm in Waterview Bay, today’s Mort Bay. At its peak, the firm employed about 1,300 workers. Among them were skilled engineers, boilermakers and shipwrights, who brought with them the traditions of British trade unionism, e.g., the Amalgamated Society of Engineers (ASE), whose Balmain branch opened in the 1860s, as one of the earliest in the country.

Other large firms in the area included Balmain Gas Company, Booth’s Sawmills, the Glebe Island Abattoir, and Elliott Brothers. They benefited from increasing connectivity, e.g., regular ferry services as well as the opening of Pyrmont Bridge, and transformed the waterfront dramatically. Increasingly, the workers were housed locally in narrow tenement houses, often part of developer schemes. Most of these still stand today (but have often been extended and renovated beyond recognition).

A tight-knit working-class environment developed. There is a grit in these streets. People were poor if not hungry, and they sought relief in the many pubs and social halls scattered across the peninsula. There were at one point more than 50 pubs in the area, with about 19 or so still open today, depending on how you count them.

With increasing industrial variety, other unions became active on the peninsula, and met in these pubs. The most iconic moment occurred perhaps in 1891, when the Labor Party formed at the Union Hall Hotel on Darling Street (still standing). Local union leaders were seeking political representation after two strikes had failed to be resolved by negotiations. Of the 35 candidates fielded in the 1891 New South Wales elections, 35 were elected. Standing outside the hotel now, it’s striking to imagine the debates and frustrations of workers seeking a voice back then.

The federal government encouraged overseas companies to apply for factory space in Balmain in 1901. As a result Lever Brothers (founding part of Unilever), Balmain Collieries (a coal mine) and the Balmain Power Station began operating in the area. By now the peninsula had become a powerhouse of industrial production.

Besides the large industries, there were countless small iron sheds and small warehouses. This mixing of industry types made Balmain special compared to other residential suburbs. I was instantly reminded of my work on industrial clusters in Tokyo, especially Sumida and Ota. Manufacturing and residential growth went hand in hand. Local agglomeration economies certainly played a role, as did the increasingly deep pool of skilled labour.

The large companies continue to have the biggest impact on the urban landscape in Balmain. Take Lever, for example: Its factory was spread out over various large buildings and chimney stacks that dominated the skyline around today’s Reynolds and Hyam Streets. They used primarily coal, copra (the white flesh of coconuts), and coconut oil, and produced several of their well-known brands here, e.g., the washing detergent OMO. The factory employed more than 1,000 workers, and included a tennis court and bowling green for their enjoyment.

Aerial view of the Lever site, see Punch Park for geographical reference. From the State Library of NSW archive

The factory closed in 1988, and its buildings were demolished in 1996 to make space for residential developments. We moved into an apartment in the Waterdale complex in 2023 and lived here for 18 months. All these redevelopments are pleasant, but generic.

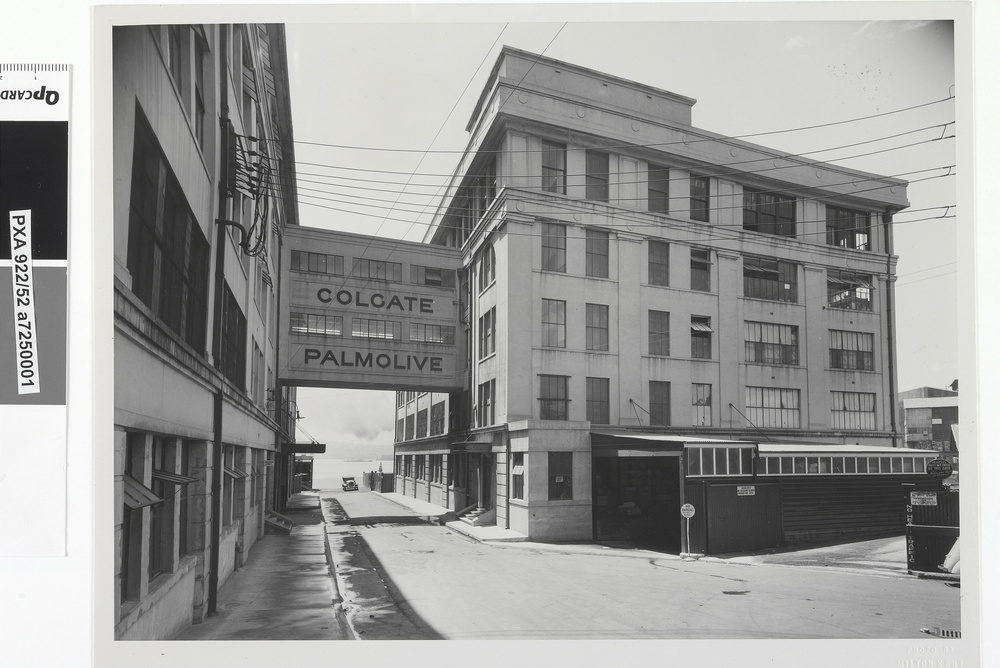

Another company producing soap and other household chemicals on the other side of the peninsula was Colgate Palmolive, whose factory in Waterview Bay was converted into an apartment building in 1997–in one of the only old industrial buildings’ adaptive reuse projects. (Photo credit State Library of NSW)

The Power Station near the Drummoyne Bridge was demolished in 1998 and made space for today’s Balmain Cove development. Elliott Brothers became Balmain Shores.

This is the former Balmain Power Station, today’s Balmain Cove development. From Flickr user dunedoo

This is the Elliott Brother site next to the power station, from the State Library of NSW archive

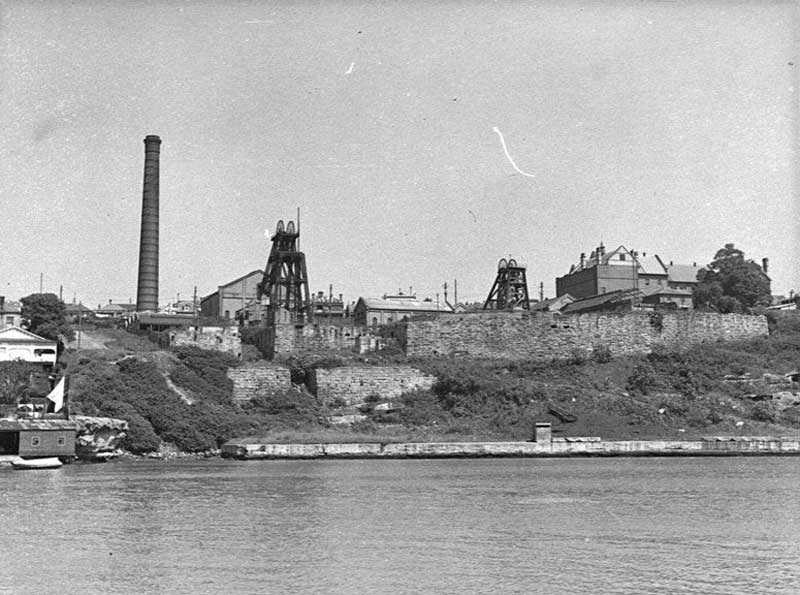

The coal mine next to Birchgrove Public School mined its last coal in the 1930s. Almost unbelievable today, but the shafts went down deep under the Harbour, where there were significant coal deposits. By 1999, more than 100 townhouses were completed in the mine’s location (photo source).

These were only the biggest of these tabula rasa redevelopments. They replaced one extractive land use with another.

Amid such erasure, very little remnants of the area’s industrial past remain today. Among them are the Balmain Shipyard in Waterview Bay which still maintains Sydney’s ferries. Just a few hundred meters along the bay are the Waterview Wharf Workshops, whose colourful buildings house various enterprises, both maritime and not, among them also some interesting non-profit undertakings.