Written with Elliott and Manu on the occasion of YAG’s 10th anniversary. Published in Caravanserai, the magazine of the Royal Society for Asian Affairs (RSAA). Click here for the article’s PDF print version.

More than ten years ago, you could see us wandering the streets of Yangon with camera and notepad in hand. Yangon seemed to be waking up from a long and uneasy sleep. A few years earlier, in 2010, Myanmar had begun opening up in a staged liberalisation process after several decades of self-imposed isolation. Its former capital was cautiously re-entering the global imagination. There was a palpable sense of change in the air.

We channelled this moment into a book: Architectural Guide Yangon. Published in 2015, it catalogued 110 buildings across the city, from before the arrival of the British to the rich and varied colonial heritage architecture. It also chronicled important works from after Burma gained independence in 1948, up to the present day.

As we were a team of two social scientists and one architect, our book was by default multidimensional. We used the built environment as a stepping stone to discuss the city’s tangled and complicated history, present and future.

It is now clear that we were documenting a city at the mid-point of its brief liberal period. With hindsight, the book took on an archival quality: a record of Yangon’s built environment at a moment of civic optimism and rapid transition, several years before the military junta putsched itself back into power.

Despite the uncertainty that now surrounds the city four years into the coup, we hope the guide will remain useful — as a reference point for those who may one day return to the work of protecting and understanding Yangon’s architectural heritage.

Yangon has Asia’s largest coherent ensemble of colonial-era buildings. But it is not just the impressive collection of buildings from 1852 to 1948 that make the architectural heritage of the city so unique. Let us go on a short tour to understand the rich tapestry of the city’s built environment.

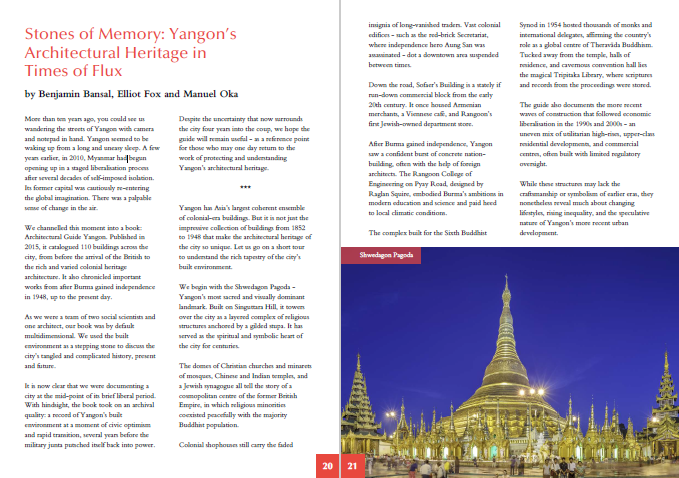

We begin with the Shwedagon Pagoda — Yangon’s most sacred and visually dominant landmark. Built on Singuttara Hill, it towers over the city as a layered complex of religious structures anchored by a gilded stupa. It has served as the spiritual and symbolic heart of the city for centuries.

The domes of Christian churches and minarets of mosques, Chinese and Indian temples, and a Jewish synagogue all tell the story of a cosmopolitan centre of the former British Empire, in which religious minorities coexisted peacefully with the majority Buddhist population.

Colonial shophouses still carry the faded insignia of long-vanished traders. Vast colonial edifices — such as the red-brick Secretariat, where independence hero Aung San was assassinated — dot a downtown area suspended between times.

Down the road, Sofaer’s Building is a stately if run-down commercial block from the early 20th century. It once housed Armenian merchants, a Viennese café, and Rangoon’s first Jewish-owned department store.

After Burma gained independence, Yangon saw a confident burst of concrete nation-building, often with the help of foreign architects. The Rangoon College of Engineering on Pyay Road, designed by Raglan Squire, embodied Burma’s ambitions in modern education and science and paid heed to local climatic conditions.

The complex built for the Sixth Buddhist Synod in 1954 hosted thousands of monks and international delegates, affirming the country’s role as a global centre of Theravāda Buddhism. Tucked away from the temple, halls of residence, and cavernous convention hall lies the magical Tripitaka Library, where scriptures and records from the proceedings were stored.

The guide also documents the more recent waves of construction that followed economic liberalisation in the 1990s and 2000s — an uneven mix of utilitarian high-rises, upper-class residential developments, and commercial centres, often built with limited regulatory oversight.

While these structures may lack the craftsmanship or symbolism of earlier eras, they nonetheless reveal much about changing lifestyles, rising inequality, and the speculative nature of Yangon’s more recent urban development.

Writing our guide was not straightforward. Reliable information on many buildings was scarce or scattered. We spent countless hours in distant archives and specialist libraries, piecing together fragments of architectural and political history.

Equally vital were the insights shared by Yangon’s residents — shopkeepers, artists, architects, and civil servants — whose lived experience often filled the gaps that official records left blank.

Many of the people we interviewed were already elderly at the time. Their ranks have since thinned further, and with them, the number of living eyewitnesses to Yangon’s post-independence history continues to dwindle.

When our book was published in 2015, Myanmar’s liberal period was at its height, and change was happening in front of our eyes. Mobile phones were becoming commonplace where just two years before, telephone operators offered calling services from countless roadside stands.

The atmosphere in the city of five million people was one of cautious possibility. Civil society was emboldened, public discourse was flourishing, and there was a palpable sense that more reforms — legal, political, and urban — were just around the corner.

Our tone was deliberately curious and engaged, perhaps gently optimistic. We sought not to celebrate a new Yangon prematurely, but to document what was there, and what could be lost if change came too fast or too carelessly.

The liberal period also helped spawn the Yangon Heritage Trust (YHT), which championed a vision of urban preservation that defied the tabula rasa approach seen elsewhere in Asia. Rather than bulldoze the past to make way for shopping malls, it argued for adaptive reuse — for the possibility of living amid history.

YHT undertook detailed surveys of thousands of historic buildings, developed conservation area plans, and advocated for legal protections and zoning reforms. Its blue plaque program began marking notable sites across the city, while training programs nurtured a new generation of heritage professionals.

Among the high points of this movement was the partial opening of the Secretariat to the public for the first time in decades. When US President Barack Obama visited Yangon in 2014, he made a symbolic walk through its courtyard with the YHT’s director Thant Myint-U, bringing international attention to Yangon’s local heritage. In 2016, the YHT published the landmark “Yangon Heritage Strategy” as a culmination of their work to date.

Some of the post-independence buildings we featured in the guide were getting a facelift, including the Nat Mauk Technical High School, also designed by Raglan Squire in the 1950s. Its modernisation was funded by the Singapore government to turn it once again into a vocational school, supplying the tradespeople needed to put Myanmar’s ambitions into stone.

Several years later, this story came to an abrupt stop.

First came COVID-19. Yangon, like cities everywhere, fell quiet. International tourism all but disappeared. Restoration work slowed, walking tours and heritage events were suspended.

Then, in February 2021, came the military coup. Protests and the ensuing crackdown by the junta left the city reeling. A massive economic crisis erased many of the gains made in the preceding liberal period.

With the return to military rule, the Tatmadaw’s uneasy relationship with the city’s layered past reemerged: the junta had long perceived Yangon as too colonial, too urban, too cosmopolitan and famously moved the nation’s capital to Nay Pyi Taw in central Myanmar in 2005.

While Yangon’s Buddhist sites were selectively showcased, the tangled histories of synagogues, mosques, merchant houses, and civic halls proved harder to co-opt for the army’s lopsided national narrative.

Reforms have since been declared null and void. After the coup, Myanmar’s property and land tenure systems have fallen into legal uncertainty, with civilian courts no longer functioning independently. Leases, preservation covenants, and planning frameworks can now be disregarded by military fiat, leaving heritage buildings especially vulnerable to expropriation or unregulated development. Thus, much of the work to protect and promote Yangon’s heritage has been thrown out the window, at least for the time being.

What does this mean for Yangon’s heritage buildings? Many are still there, of course. But heritage preservation requires more than structures — it needs caretakers, storytellers, institutions. It also needs time to see society build a consensus that it is worthwhile to protect them. The current regime’s extractive nature and its lack of capacity might nourish a growing indifference and nihilism.

And yet, we remain hopeful. Perhaps not for immediate change, but for the idea that these buildings still matter. They still stand. And someday, someone else will pick up the thread.

If you visit Yangon in the future, take a copy of the guide. Walk the streets with it. See what’s changed. See what remains. In doing so, you join a long tradition of readers, writers, citizens, and wanderers trying to make sense of a city that refuses to be forgotten.

Note: The book’s first edition with DOM publishers is currently out of print. Interested readers are guided to the website www.yangongui.de for a full online version of the book. The authors are hopeful that they can one day reunite to work on a second, updated edition of the guide.

Benjamin Bansal is a development economist based in Sydney, Elliott Fox manages communications for an international charitable fund in London, and Manuel Oka is a practicing architect in Munich, Germany.