My university, as part of their fantastic summer program, kindly organized a tour to the Urban Renaissance Agency Technology Research Institute the other day. The most relevant aspect to my research was the Housing Apartment History Hall. Here, some landmark apartments from what to most appear like faceless concrete blocks have been lovingly rebuilt.

Inside Maekawa’s Harumi Apartments

UR is the successor organization to the Japan Housing Corporation, which began operations in 1955 to address the nation’s severe housing shortage. Barely recovered to pre-WWII levels, Japan’s cities — above all Tokyo — now burst at the seams of a rapid influx of population from the countryside as a result of the economic boom.

I hope to write a little more about the motivations to set up the JHC when I get to the relevant parts of my research. Within a few years, the first ubiquitous danchi communities were built. Ann Waswo’s Housing in Postwar Japan: A Social History and The Lives We Longed For: Danchi Housing and the Middle Class Dream in Postwar Japan by Laura Lynn Neitzel are great English-language sources on the topic.

Public housing in Japan never reached the proportions it would in postwar Europe, and never accommodated more then 10% of the population. Instead, Japan by the early 1960s had become a homeowner society, with the residual renting in the private market; as well as relying on company-supplied housing, which rivaled public housing for third spot in terms of tenure.

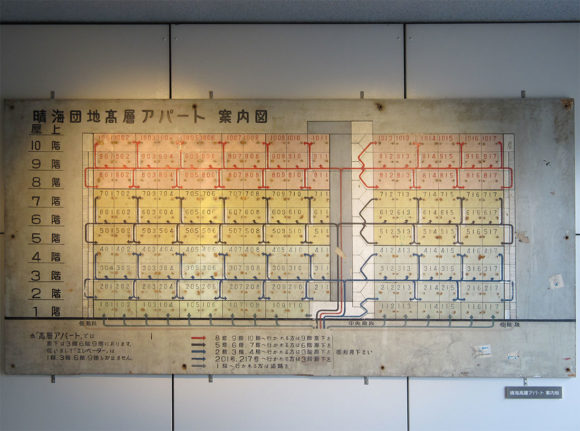

The research institute has been around for many decades. Their efforts have not only informed public housing technology but helped advance living conditions in multi-unit apartment buildings across the board. The ominous 108-meter tower visible far away the UR’s site in Hachioji was built in the 1960s to facilitate research on tall structures, e.g. how to optimize water systems in high-rises. With this research now largely being done, the tower has become obsolete and is in the process of being dismantled.

Other areas on public display included the skeleton infill section. Here, UR goes against the continuous scrap-and-build by borrowing from metabolic structures (not unlike what Kikutake had foreseen several decades ago). The main structure of the building is built to last a hundred years, what can be changed regularly is the inside fitting. We saw a few remodeled apartments.

See the flat electric wiring?

My fellow students reported that it all seemed rather low-tech in comparison to the tour they got at Shimizu Corporation while I was in Europe. One cool gimmick were totally flat electric cables that make wiring a lot easier and less space-intensive than what is usually the case. For all sorts of reasons, skeleton infill is a big topic in Japan and seems like a more eco-friendly way forward.

Another area we visited was dedicated to the harmonious co-existence of tenants in relatively crammed conditions: yes, soundproofing. We saw our instructor demonstrate dropping spoons and playing indoor-basketball on the floor above us, all on different material. Needless to say, insulation does wonders. The same went for loud music being played behind drywalls with special glass-fibre.

Front of the history museum

The most interesting part of the tour was the museum. The first reinforced-concrete public housing buildings went up 90 years ago, after the Great Kanto Earthquake. They were built by dojunkai, a predecessor organization to UR. It realized several projects in the 1920s and 1930s, before the agency being wound down in 1942.

Inside the Daikanyama dojunkai

The museum has two apartments of the Daikanyama dojunkai installed. One single and one family unit show the architectural feat that these buildings represented. They married the language of modern public housing with Japanese design sensibilities. Flooring was tatami-only, and facilities cutting-edge for their time. It is a shame that today, none of these buildings survive except for a building front in Omotesando and two single-family homes in Daikanyama.

The postwar era section’s most interesting exhibit are the two apartments from the Harumi Apartment building, designed by Kunio Maekawa (see the photo at the top of the post, and the floor plan below). He was clearly inspired by his teacher Le Corbusier (whose atelier he worked in), in particular his Marseille unité d’habitation. The two apartments, in particular the more spacious one with direct elevator access, were remarkable. It just looked extremely thought through (the large unit had 42 square meters) — and one has to wonder if public housing has much advanced since.

To finish, two more shots from another postwar danchi evoking your guilty showa-era nostalgia: