Rather than dumping a whole 8,000-word essay on this blog, I thought that it makes more sense to fast forward straight to the conclusion. Please read below the jump what I found out about the impact the Allied Occupation of Japan between 1945 and 1952 had on Tokyo’s urban development. I may chop up the main body of the text and post it on the blog in segments if there is any interest. Just drop me a line!

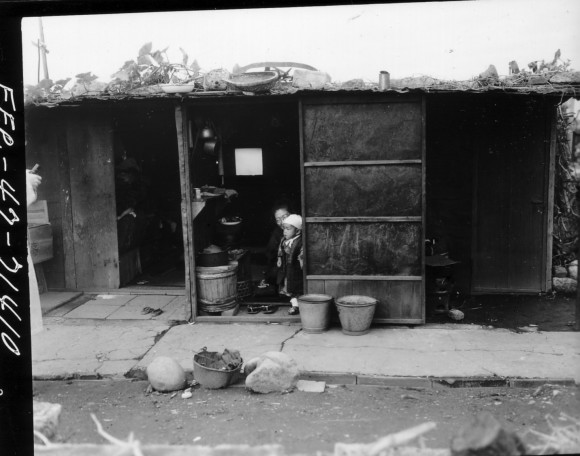

Ebisu shacks 1945 – from Japan Air Raids

This paper has attempted to shed some light on the Occupation period and the ways in which the Allied presence and their policies shaped Tokyo’s urban fabric. The threefold division into the spatial, institutional and subtle channels along which this occurred could not avoid certain overlaps between them. This is perhaps also true of the timeframe under scrutiny. The highly fluid 1945-1952 period may be subdivided into several chapters, and yet also needs to be seen as continuous with the prewar years. Moreover, many effects of the Occupation took several years longer to fully play out in urban Japan, especially when it comes to the influence of American consumer culture.

Nonetheless, as the limited sample of case studies provided in this paper already shows, both direct and indirect impacts of the American-led Occupation on Tokyo were significant. Preceding the peaceful ground-level invasion was the incineration of large swathes of urban land. The imposition of foreign military rule changed the face of Tokyo profoundly. Military bases and a ‘Little America’ at the spatial heart of the city, just outside the traditional nexus of power — the Imperial Palace — would become important constituents of the bombed-out city. Reconstruction over the following years had parallels with the one following the 1923 Great Kanto Earthquake. Given that Tokyo’s fate was shared by dozens of other Japanese cities, however, resources were now even scarcer and progress even more sluggish. From what can be ascertained from SCAP/GHQ sources, the Allied were at best indifferent to the housing shortage. At worst, their directives prevented the more extensive and faster construction of emergency shelters. The fact that Tokyo could avoid the unchecked growth of slums as well as social turmoil as a result is interesting and warrants further research.

On a more institutional level, some of SCAP’s reforms had strong ramifications for urban space. However, had they been realised as planned and without the Japanese side’s lobbying against some of their key provisions, Tokyo would most likely look different today. More coherent and extensive urban planning and public works could have been made possible had landowners’ rights not been as guarded as in the 1947 Constitution’s Article 29. More autonomous local governments would have perhaps reined more into unchecked urban growth and pollution during the high-speed growth era than a central government which prioritised economic development over citizen’s welfare, at least until the late 1960s. However, the lack of local autonomy may have eventually also played out in Tokyo’s favour. Lax to non-existent zoning rights in the first two postwar decades were arguably behind Tokyo’s significant flexibility and adaptability to grow organically. It can be argued that these were likely the result of an indifferent and institutionally overstretched central government, or in Tokyo’s case the metropolitan authorities. This area, too, warrants further research given its relevance to the urban development discourse.

Some of the most lasting legacies of the Occupation period fed through in a more subtle fashion. The American influence, emanating from within the military bases and the rest and recreation areas, above all Ginza, would help shape the city’s culture in music, dance and fashion. The early postwar years’ “cultures of defeat” (Dower 1999) also included the “pan-pan” girl. She was synonymous with the proliferation of the sex trade fueled by the Allied troops. It can be argued that its results still bear on Japanese urban space, especially around its train stations. American consumption culture infiltrated Tokyo with the Allied Forces’ presence, especially in Ginza, Roppongi and Harajuku. Although they have since been complemented by many other areas of similar if not higher social standing, these areas remain important centres of consumption and popular culture. Lastly, this paper has looked at how the discourse on postwar architecture was influenced by the seminal Occupation-era works of Antonin Raymond and later even Swiss-French master Le Corbusier. The international appeal of Japanese architecture today cannot be seen in isolation from this important time period.

The Occupation period produced a historical moment in time that was without precedent, it was “intense, unpredictable, ambiguous, confusing and electric”. It was markedly different than that of Germany, because “it lacked the focused intensity that came with America’s unilateral control” (Dower 1999: 23). The cities, above all Tokyo, were the arena for these encounters between victors and defeated. All too often, when the Japanese capital is analysed in the social sciences, the focus on it begins with the onset of rapid economic growth in the early 1950s. As this paper has shown, however, much is to be gained from a closer look at the Occupation period from 1945-1952.

***

Herewith the references, many of them are available online:

- Condry, Ian 2002, “Review of Blue Nippon”, in Current Musicology, nos. 71-73 (spring)

- Cullen Green, Michael 2010, Black Yanks in the Pacific: Race in the Making of American Military Empire After World War, Cornell University Press

- Day Cole, Alexandra, “Jazz in Japan: Changing Culture Through Music”, Boston College Electronic Dissertation, available online: http://hdl.handle.net/2345/bc-ir:104170

- Dore, Ronald Philip 1958. City life in Japan: a study of a Tokyo ward, Berkeley: University of California Press

- Dower, John 1999, Embracing Defeat: Japan in the Wake of World War II, The New Press

- Fedman, David and Karacas, Cary 2014, “The Optics of Urban Ruination: Towards an Archeological Approach to the Photography of the Japan Air Raids”, in Journal of Urban History, 1-26

- Hein, Carola 2003. “Introduction” in Hein, Carola ed. Rebuilding urban Japan after 1945, London: Palgrave Macmillan

- Ichikawa, Hiroo 2003. “Reconstructing Tokyo: the attempt to transform a metropolis” in Hein, Carola ed. Rebuilding urban Japan after 1945, London: Palgrave Macmillan

- Kaplan, David and Dubro, Alec 2003, Yakuza: Japan’s Criminal Underworld, University of California Press

- Loeffler, Jane 2010, The Architecture of Diplomacy: Building America’s Embassies, Princeton Architectural Press

- Lum, Melissa 2007, “A Comparative Analysis: Legal and Cultural Aspects of Land Condemnation in the Practice of Eminent Domain in Japan and America”, in Asian-Pacific Law & Policy Journal, Vol. 8, Issue 2 (spring), 456-484

- Marx, David 2011, “The Original Roppongi Tribe”, in Neojaponisme, available online

- Ministry of Finance, Fiscal and Monetary Policies of Japan in Reconstruction and High-Growth 1945-1971, available online

- Motooka, Nobuhisa et al 2004, “Small House Projects in Japan: Housing Experiments for Sustainability and Open Building Concept”, available online

- SCAP 1944: Local Government in Japan, NDL bibliographic ID 024057573, available online

- SCAP 1946/1, Control of Population Movements, NDL bibliographic ID 000006848071, available online

- SCAP 1946/2: “Housing Corporation”, in reports of the Japanese Government to SCAP, NDL bibliographic ID 000006797710

- SCAP 1947, Local Autonomy to Local Taxation Systems, NDL bibliographic ID 000006699288, available online

- SCAP 1948, Japanese Housing Requirements, Research and Programs Division, NDL bibliographic ID 000006812372

- SCAP 1950/1, “Petition from Ohta Ward for More Local Autonomy”, NDL bibliographic ID 000006699296, available online

- SCAP 1950/2: “Housing Loan Corporation, in reports of the Japanese Government to SCAP, NDLL bibliographic ID 000006792972

- Sorensen, Andre 2002. The making of urban Japan: cities and planning from Edo to the 21st century, London: Routledge

- Stars & Stripes 26 March 1948, “First Year Celebrated in Washington Heights”, available online

- Takemae Eiji 2002, Inside GHQ: The Allied Occupation of Japan and its Legacy, London: Continuum

- Taylor Atkins, E. 2001, Blue Nippon: Authenticating Jazz in Japan, Durham, N.C.: Duke University Press

- Tokyo Metropolitan Government 1957. “Tokyo Statistical Yearbook”, available online

- Waswo, Ann 2002, Housing in Postwar Japan: A Social History, London: Routledge

- Watanabe, Hiroshi, 2001, The Architecture of Tokyo, Edition Axel Menges

- Yoshimi, Shunya 2006, “Consuming America, Producing Japan”, in Garon, Sheldon and Maclachlan, Patricia, The Ambivalent Consumer: Questioning Consumption in East Asia and the West, Cornell University Press

- Yoshimi, Shunya 2008, “What Does “American” Mean in Postwar Japan”, in Nanzan Review of American Studies, Vol. 30