One of the two presentations I gave on the occasion of the “Inheriting the City” conference in Taipei last week was on Yangon’s heritage discourse. While I am still debating whether to write it up into a full-blown paper, herewith a brief summary for the records.

Tripitaka Library

The inspiration for this talk came from the work on the Architectural Guide, but also from a recent comparative paper I wrote on Yangon and KL and the work on Yangon’s urban history a friend of mine is doing.

The title of the presentation was “What is Yangon’s Story?” — broadly provocative in order to question the narratives that are being followed in today’s heritage debate, or better, to highlight which narratives are currently underrepresented.

I believe these are the “Indian” character of Yangon’s colonial-era period as opposed to its often-touted cosmopolitanism as well as a lack of post-independence history. The reason these narratives are absent lies in them being politically contentious, despite the recent opening and liberalisation of the country. The contention with the city’s character also explains the lack of political buy-in to heritage preservation as well as the proliferation of a rather generic “thin heritage” discourse.

Expecting a non-initiated audience, I walked people through the key dates in Yangon’s history, starting from Dagon’s foundation as a small fishing village around the turn of the first millennium. I stressed that until the British make it the capital of their colonial possessions in Burma, Dagon and/or Yangon has no history of being a political or commercial centre. However, the presence of the Shwedagon Pagoda makes it the spiritual focal point in the region and beyond.

The three Anglo-Burmese Wars establish Yangon on the map and gradually increase its importance. The city is reconstructed after the second war, and with the annexation of Upper Burma following the third war, the colonial apparatus grows tremendously, as does the economic prowess of the city thanks to port facilities by the river.

Moving on, I highlighted 1916, 1920 and 1930 as important dates bearing on Yangon’s “story” — they mark the first Shwedagon Pagoda protest with a nationalist bent, the University Boycott and the Race Riots, respectively. The Second World War comes to Yangon with Japanese bombardments in 1941 and the invasion the following year. The same period sees the exodus of hundreds of thousands of Indians, mainly via the overland route.

Burma receives its independence from Britain about half a year after the architect of independence, young General Aung San is assassinated in 1947. Civil war and chaos prevent an “orderly” post-colonial nation building, although the Sixth Buddhist Synod offers a rare glimpse into those dynamics in Yangon. Ne Win putsches himself to power in 1962, and with it, so the narrative goes, begins Burma’s long and fateful decline into economic and political isolation.

This process is not without its detractors, though, and important protests break out in Yangon in 1962, 1974, 1988, 1990 and 2007. These lead to the creation of the SLORC and the YCDC in 1990, the construction of several of Yangon’s most eccentric buildings, as well as the relocation of the capital to Naypyidaw in 2005, to name but a few of the consequences relating to Yangon’s built environment.

After this rather long historical detour, and using Manuel’s photos, I highlight what is at stake in Yangon today: Widely thought to hold Southeast Asia’s most coherent and intact colonial-era cityscape, left largely intact but crumbling after decades of international isolation.

Besides the vestiges of the Empire (Secretariat, Custom House, etc.), there are many imposing commercial buildings (Sofaer’s, Strand Hotel), a striking body of religious architecture (pagodas, temples, mosques, churches, etc.) and less tangible heritage in the form of Chinatown, Indiatown, tenements around pagodas, etc. Many of these are threatened by demolition, improper restoration, neglect or gentrification. How can this amazing heritage be safeguarded?

Many players are active in answering this question. They include the YHT, YCDC, JICA, Western embassies, NGOs such as the Turquoise Mountain Foundation, the World Monument Fund, etc. As Kecia Fong says, “[c]ollectively these actors shape the language, discourse, and materiality of heritage and wittingly or not they bring with them the underlying ideologies that inform their processes of knowledge production, value systems, aesthetics, and accepted methodologies.“

Moving on the the core of my presentation, I argue that there are certain underrepresented narratives in the heritage debate.

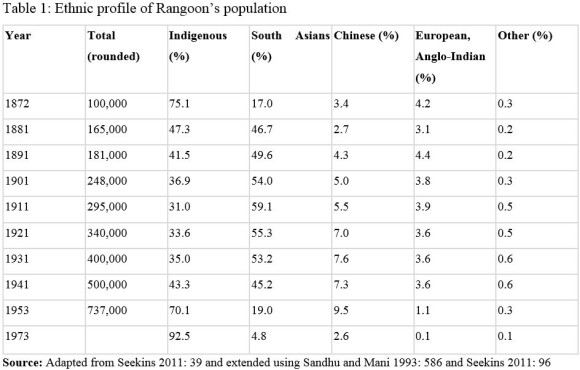

I think that in contrast to the often touted cosmopolitanism, Yangon was in fact an “Indian” city throughout much of the period the heritage architecture dates from. This complicates making a case for heritage preservation today. Much of Burma’s early nationalism and nation building coincided with a (perhaps justifiable) rejection of this Indian character of the city. The ethnic homogenisation of Yangon, starting off with the 1930 riots, continuing with the 1941/42 exodus and the post-war chaos culminated in Ne Win’s 1964 nationalisation policies. Here is the census data I showed to underline my point. They show that Yangon was a majority Indian city from the late 19th century onward until the equally rapid reversal took place.

This issue is alive, if simmering below the surface, today. Thousands of stateless Persons of Indian Origin (PIO), unresolved ownership issues involving heritage architecture, as well as a full historical account that remains to be written are testament to that.

Moreover, as highlighted above, Yangon provided the stage for several protests challenging the regime. These alienated parts of the political elite from the city, a process that, we argue, eventually led to the relocation of the capital from Yangon to Naypyidaw in 2005. The lack of officially sanctioned narratives with Yangon at the centre may also explain the political elites’ disinterest in the heritage discourse.

In addition to the above, Felix Girke’s paper on “thick and thin heritage” is worth a read. It laments a lack of deeper engagement with particular buildings’ histories in the heritage debate. The abstract of his paper outlines his main contention:

Many colonial-era buildings in Yangon stand neglected or deserted. With global resonance, the Yangon Heritage Trust has spearheaded efforts to conserve the city’s unique heritage. But rather than focusing on particular histories of buildings and local perspectives on them, the dominant view of “thin” heritage propagated today emphasises age, aesthetics and generalised importance. (…) The multi-vocal heritage discourse in Yangon today is in danger of being monopolised by a marketable generic idiom.

There is much to chew on in the article, and the Yangon Heritage Trust may come out a little badly by just quoting Felix’s abstract. The key is for us to have a deeper appreciation of each building. It is equally important no to perpetuate and internalise the rather superficial level of discourse one has gotten used to via the myriad of rather generic pieces appearing in the international media. All the while, urban history accounts are still thin on the ground, and it is difficult to build a “thick heritage” narrative coherently throughout the city.

As becomes obvious from the above though, much of this colonial-era and post-independence history is contentious. While Myanmar is opening up politically, old elites are still in positions of power. Does “heritage” require some form of consensus on the city’s and people’s identity? Given the blood that has been spilled on Yangon’s streets, what is the role of truth and reconciliation?

Comments and feedback more than welcome!

Ouch, the abstract itself is also generalising YHT’s efforts in heritage conversations. If one joins my tours for the local as well as the international visitors, one will see that one of the main messages is how cosmopolitan the city was, explaining the diverse communities and multi-religious aspects of the city.

I’ve heard that Yangon was the first city in South-East Asia which had the first-ever underground parking lot. But I couldn’t find which was the building it was? Can you help to advise? Thanks!

Hi Kevin, this would probably be the Standard Chartered Bank on Lower Pansodan, built just before the outbreak of WWII.