During the research for our Yangon Architectural Guide, we came across this American architect. He built the Tripitaka Library (Pitaka Taik), also known as the Great Buddhist Library in Yangon. Some scribbles below the jump.

Tripitaka Library, photo by Manuel Oka

Today the place is a little out of the way next to the Kaba Aye Pagoda north of the downtown area. A huge man-made cave is another sight out here that makes the trip here worth it. The library is to the north of both pagoda and cave, and behind a fence and set amid a slightly overgrown park.

We cover the history of the library and the adjacent building in quite some detail in our book; they were purpose-built for the Sixth Buddhist Synod, held in Rangoon between 1954 and 1956. The library itself was finished a few years later, presumably in 1961. I found a map of the complex from a 1956 book on the synod.

In this post I want to jot down some biographical information on Polk, in which I rely on his and his wife Emily’s autobiography, India Notebook: Two Americans in the South Asia of Nehru’s Time, and his Building for South Asia as well as some online sources, in particular Berkeley’s Environmental Design Archives.

Benjamin Kauffman Polk was born in Iowa in 1916. He attended Amherst College, the University of Chicago, and studied structural engineering at the University of Iowa. He practiced architecture in San Francisco only for a short time after the war, during which he served in the US Army. He returned to university by way of the UK, where he earned a Master’s equivalent in regional development.

From India Notebook comes this passage:

How did my wife and I come to India? There is no single answer. It was 1950. I took a diploma in regional planning in London (…) The world is round. We were in 1952, in Europe. So, home to California then, by way of India. And fate and fortune led us to find there another home.

One of Polk’s first major commissions as an architect was actually in Pakistan. While fellow architect Raglan Squire also tried his hand at a commission here (his winning entry for the Jinnah Mausoleum did not get built in the end), Polk ended up designing the Polytechnic Institute in Karachi. The institute was sponsored by the Ford Foundation, which was extremely active in the region around that time (my co-author Elliott spent hours in their archives outside of New York City).

The Ford Foundation commission opened further doors for Polk, this time in post-colonial Burma. The Tripitaka Library, important part of U Nu’s pet project, the Sixth Buddhist Synod, was to be one of his major legacies. I have written about the architecture and the place on Uncube Magazine, and there is not much point repeating much here. What I can do though, courtesy of Abhinav Publishers in Delhi, is post the photos here that accompanied my article and which are taken from Polk’s Building for South Asia:

Benjamin Polk and U Nu standing in the main library rotunda. Burma’s first post-independence prime minister was a devout Buddhist, using religion as an expedient tool for nation building.

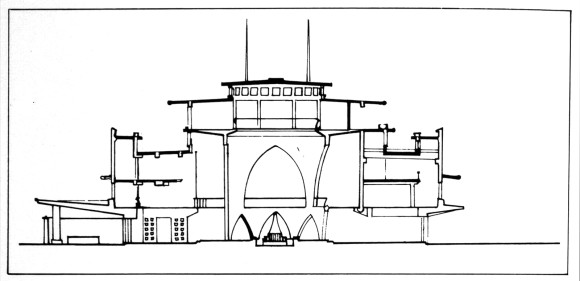

A cross section of the core building.

Design Model. The library’s three wings contain a public library, auditorium and religious museum. The central core is reserved for scholars and monks, a sanctuary for study and meditation.

The front of Tripitaka Library, shortly after its opening in the early 1960s. The landscaped garden, centred around the artificial lake, give the building a more stately impression than today.

Back in India, Polk built the Jallianwalabagh National Memorial commemorating the 1919 massacre in Amritsar, in which British troops killed more than 1,000 pilgrims. This was a highly symbolic project, the first monument of its kind to be built in post-independence India. It shows Polk’s signature style of engaging deeply with Indian forms and getting a deep understanding of the historical significance of the assignment.

The work is in solid red sandstone ashlar – none of the thin veneers that characterize both Muslim and modern Indian work (…). The monument is built to last the centuries, a forty-five-foot high sikhara form, framing the relief pattern of a flame of martyrdom. (…) This monument beckons to brotherhood, and there is no echo of bitterness; Indian forms are given a new meaning.

Another main commission was the Royal Palace in Kathmandu. King Mahindra of Nepal had been made aware of Polk through the Tripitaka Library in Yangon. This led to further work for USAID in the country, which was implementing an education program then. What an interesting contrast for an architect to build royal palace and school buildings at the same time.

I make no apologies to those who think these expensive public symbols are out of place where people are in poverty. On the contrary, tangible rallying points are more than ever needed in new nations. And especially this is true in Nepal. Beautiful ancient Hindu-Buddhist temples are to be seen today throughout the country – the glory of Nepal. They invariably fit the site, and their splendid ornament is functional, integral to the form and structure. It is not something merely added to it. ‘Less’ is most certainly not ‘more’ – contrary to the dictum of the modernists.

Polk is the lesser-known of the two Americans in the Stein-Polk-Chatterjee partnership, which at some point in the 1950s, was the largest architectural practice in Asia. The other American, Joseph Allen Stein, is portrayed in this Outlook India article. With Lutyens, he is probably the most important (foreign) architect to have built in the Indian capital. The area near Lodi Gardens is still affectionately known as “Steinabad”.

And yet Polk, also thanks to his commissions in Pakistan, Burma and Nepal, should be remembered equally well for synthesising modernism with a uniquely South Asian formal expression of tradition. In an age of conformist and often bland architectural language, this is perhaps his most important legacy.

It appears that Polk left India in 1963, although what he did between then and taking up a post at California Polytechnic State University in San Luis Obispo is not known to me. He and his wife returned to India for an eight-month stay in 1980 after Polk had retired from his teaching position. They then lived in Salisbury (UK) for another ten years before returning to California, where Polk passed away in 2001.

I vaguely remember meeting Polk while in Delhi in 1959-60. Most importantly I believe he introduced me to the concept of “place” in architecture. Have not been able to find article he may have written then. Woukd appreciate any reference.

Donlyn, I am the nephew of Benjamin Polk, have visited many of his creations in India. I believe the work you are looking for is titled, “Architecture and The Spirit of the Place.”

He and his wife Emily were friends of my family and we were there to help them in the end. Ben and his wife moved to a posh assisted living(we helped them move)where he passed away not long after arriving. Emily moved back to Atascadero where she would take long rides through the area with her driver. They were amazing people and I make sure my kids will never forget them.