This blog is a sounding board and a notepad. Almost three years into writing here with varying regularity, I have hardly summed up my thoughts regarding some of the admittedly few books I read. Yet David Graeber’s Utopia of Rules and Naomi Klein’s This Changes Everything deserve some reflection.

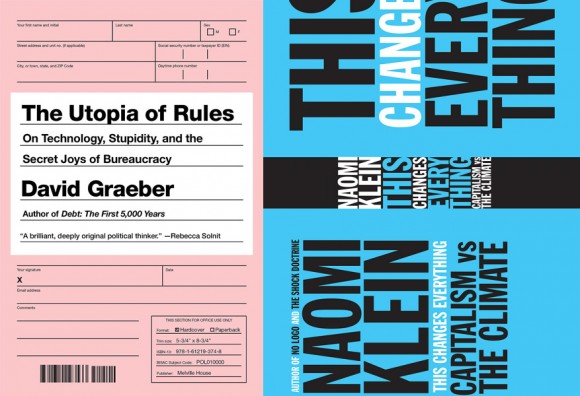

Two great covers, two great books

I read them in short succession over the summer and thought I can put them both in this post. Mainly because there is some kind of personal connection between the two, although the initial inspiration to treat them together is now somewhat lost on me, many months later. But this is a blog after all, right?

I picked up Klein’s book with some caution, and that is strange given where I hail from academically, i.e. the School of Oriental and African Studies as well as Cambridge’s department of development studies.

Growing up, I was a member of Friends of the Earth Germany, a keen ornithologist, and conducted my first semi-academic research project during school on the negative aspects of globalisation, a fiery piece whose language seemed inspired by Attac more than anything else.

Yet as my intellectual world broadened, such convictions made space for a more ambivalent understanding of the world around me. Being at a leftist university with a Marxist-leaning economics department was totally compatible with this. Dispassionate and silo-ed as the social sciences are.

Fast forward a few years and I had arrived in the corporate world. It would be too easy to ascribe the move to the political centre to brainwash. And still, that’s pretty much what happened. The complexity around me, from accounting practices to oil and gas fiscal systems at first and then emerging market bond portfolios and the wider financial world made the “yes, but…” response all too common.

I have not read Klein’s other books, but this one is not polemic nor light on substance. In fact it is meticulously researched and comprises the latest consensus views on climate science. Her team diligently went through thousands of peer-reviewed academic papers and received probably the best advice that’s out there.

Nonetheless, this book is not a dispassionate array of facts and figures to sway the reader of the merits of immediate action on climate change. It is a highly personal and political treatise on why capitalism–as we have increasingly embraced it since the 1980s–has become the main inhibitor to taking effective action against potentially catastrophic global warming. For Klein, it is the culmination of many years as a critic of corporate globalisation.

There is a great historical irony in this: when our concerns began to mount in the 1990s (and I, too, became a greenhorn environmentalist birdwatcher during weekends spent in rural East Germany), the Iron Curtain collapsed, and with it, the End of History was announced. Liberal economics and a corporate-dominated capitalism were no longer questioned in their principles outside activist circles and left-wing universities.

Just a year before the the financial crisis hit, I joined a big oil company’s finance department and worked my way through its fund management section. As Lehman fell and central banks around the world embarked on their stimuli, a wider rethink began as old certainties began to crumble.

Economics courses are now being revamped around the world, there is a stronger call for redistribution, and the political ground shows some signs of shifting, at least to the left of the centre.

At the same time much of the political middle clings onto the old orthodoxy of balanced books, and many of my friends are stepping onto the property ladder. Is this the self-perpetuating conservative society? Or am I only estranged from it because I have just moved into student accommodation in Tokyo a month ago?

Anyway, in retrospect and looking back at myself in 2007, it seems strange beginning my working life in a world in which I would have to take on a veneer of old-fashioned market conformism at the same time this concept was becoming increasingly challenged outside my office walls. In short, perhaps, I missed Naomi Klein moving into the mainstream.

I subsequently left the “corporate world” in 2012, not out of some deep-seated antipathy or crash against the wall of my inner principles. I took it rather opportunistically without too much reflection. My exit from the oil industry holds up rather well in retrospect (see Klein’s book above; I don’t think it is the industry to be in long-term, seriously). My one-year stint in development banking was not building up enough passion for me to reject my wife’s offer to go to Japan with her, on my “unsolicited” sabbatical.

And now it’s already more than three years since I left the traditional labour market. The time has both been estranging and cathartic. Estranging because once one has left the club, one feels a little stranded. Gone are the vestiges of power, gone are the paychecks, and gone is some of the authority with which one can present oneself to others. There’s no denying that.

Cathartic because the last three years have been a great ride intellectually. I connected with an entirely new field, somewhere in between urban economic history and development studies. Much of this love affair came about thanks to a six-month stay in Tokyo in 2012-13, but has found extension to places like Yangon, New York, Germany, India and even Washington, D.C.

My very own realisation of the space around me helped me reconnect with my original disciplines, development studies and economics, in a much more profound way. Travelling through India or staying in Yangon researching our architectural guide has been so much more intense than all of the frequent trips as a fund manager combined.

It is this fertile climate of self-examination that reading these two books took place. I was blown away by Graeber and deeply touched by Klein. I have finished them some months ago now as I had left this post unfinished for some while.

That makes it hard to comment on much of the substance, but easier to detect what effect they had on my thinking since. I think I have become more political and less forgiving of those pushing complexity before a straight answer, especially around distributional issues as well as climate change. I think that’s both a function of not being deeply “in” the subject matter anymore and being able to afford stronger convictions again.

There is a danger to that: having strong opinions without the backup of facts can mean slippery slopes. One ameliorating factor here is age. I have entered my mid-thirties and can better afford opinions at the expense of having every fact fact-checked.

Oh, what about Graeber, I didn’t comment on his book at all yet! This is the peril of leaving posts unfinished for too long. I feel that I have to go back and read it once more to put something here instead of this [placeholder].

If I happen never to do so, the book blew me away not only for the connections it drew between structural violence and ubiquitous bureaucracy. I loved the cultural references and political affiliations of superheroes. The history of the post office in the US. The fact that large corporates breed structures of bureaucracy Kafkaesque governments could only be proud of. Among others.