Japan’s post-war rise is often mentioned in the same breath with Germany’s spectacular economic miracle – the “Wirtschaftswunder”. For someone born on the other side of the wall in East Berlin, it is interesting to read about the less-documented relationship between economic superstar Japan and socialist East Germany during the decades of the cold war. The first installment in a set of some anecdotes is about Kajima Corporation’s export of Japanese construction practices to Berlin, Leipzig and Dresden.

Hotel Merkur Leipzig model presentation by Kajima Corporation in 1978

Kajima, this corporate behemoth responsible for some of Japan’s biggest concrete constructions (Tokyo’s first skyscraper, the Kasumigaseki Building (1968), Keio Plaza Hotel, Shinjuku’s first high-rise building (1971), ARK Hills, Mori’s first visionary city-within-the-city complex) – how come that the company’s sole international project during the 1970s is a fairly nondescript office block in downtown East Berlin?

In fact, the International Trade Center next to Friedrichstrasse station was the first of several projects the company would undertake in the socialist republic in the decade to follow.

International Trade Centre as seen from Dorotheenstrasse in 1988 (source: Wikipedia/Bundesarchiv)

Kajima’s engagement here was in line with the trend that the GDR under General Secretary Honecker was increasingly looking to non-socialist countries for trading relationships, earning the socialist state hard currency (increasingly, the GDR also asked for loans, more on that in a separate post).

The oil crisis had hit the coffers of East Germany hard – and the new mantra of the leadership – i.e. to provide East Germans with tangible improvements in living standards (also to avoid a Polish scenario) – needed above all money to buy things abroad.

While firmly embedded in the Western trading bloc, Japan signed the first official trading treaty with East Germany in 1971. West Germany’s “Ostpolitik” had made it more politically correct to deal with its socialist neighbour. In 1973, this became official: Japan recognised the “other” Germany and embassies were opened in both East Berlin and Tokyo.

And although trade with East Germany never reached the levels recorded with West Germany, some significant deals were struck. The Kajima cooperation was certainly one of them. The agreement played into the hands of the East German leadership who saw a trade centre and several hotels of international standard as part of a strategy to create an infrastructure amenable to global trade.

With its 25 stories and 94 meters in height, the Handelszentrum stands out to this day. East Berlin had a limited amount of high-rise buildings: one is the nearby Forum Hotel on Alexanderplatz, almost two kilometers away as the crow flies; the other noteworthy ones are the residential tower blocks on Leipziger Strasse.

The International Trade Centre as seen from Friedrichstrasse (source: Wikipedia/Bundesarchiv). The big white building is the now-demolished Hotel Unter den Linden

The building was designed to house foreign companies involved in trading with East Germany. In the beginning, a respectable number of 18 Japanese companies had their offices here. Today, only Bank of Tokyo Mitsubishi is left.

Kajima shipped some of the steel and other material by freighter (the “Karl Marx” sailing under GDR flag) from Yokohama to Rostock and sent engineers to oversee the construction process. It took about two years before the building was opened on 1 September 1978.

This video, while a little painful, has some amazing Kajima footage from the construction period sprinkled in throughout. The narrator speaks with a heavy Japanese accent (as does the Japanese lady picked to interview today’s tenants of the building):

The other three Kajima projects in East Germany all took place in the 1980s. All of them were hotels.

In order to earn precious hard currency, East Germany’s Interhotel operated a number of luxury hotels throughout the republic that preferably admitted foreigners paying in USD or Deutschmark. Service in these hotels (and in East Germany as a whole) was notorious, as this article from Der Spiegel attested in 1984.

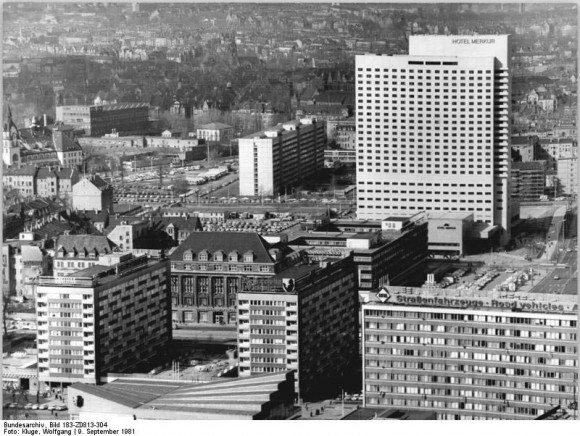

Hotel Merkur Leipzig (source: Wikipedia/Bundesarchiv)

The first one to be built was Leipzig’s Hotel Merkur. A straightforward business case, it seemed: Leipzig was the GDR’s convention centre, with annual industry fairs leading to a regular influx of hard-currency-bearing Western businessmen.

East German General Secretary Honecker tabled the deal as a present when in Tokyo in 1978. Kajima, apparently happy with how things went with the trade centre in Berlin, agreed to build the building for 16 billion yen. Ironically, most of the concrete elements were being sourced from West Berlin.

At 96 meters, it would be even be higher than the trade centre in Berlin. Its more than 400 rooms are split across the 27 floors. Even today, it is thought to be one of the best business hotels in Germany. From an architectural point of view, one could again locate its rather nondescript modern features anywhere in Japan.

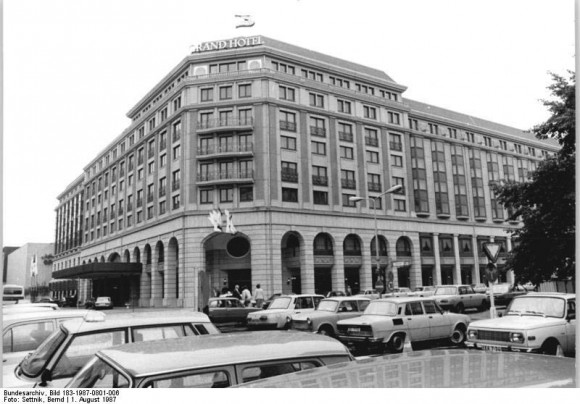

Kajima’s last two projects in the GDR, the Westin Grand Hotel (above) in Berlin and the Hotel Bellevue in Dresden, were perhaps the most “interesting” architectural projects.

Kajima put in-house architect Takeshi Inoue in charge of both of them. They represent attempts to deal with aspects of German architectural heritage, and to blend into the existing historical structure. This was in line with East German construction practice in the 1980s: one became more aware of heritage and increasingly devoted time and resources to renovations or historicist (re-)constructions (such as the Nikolaiviertel).

The Belleveue in Dresden made open reference to its baroque surroundings. The year that the hotel was opened, the restoration of the Semperoper was finalised. In Berlin, the neoclassicist Grand Hotel would mirror an early twentieth century style. Its opulence was reflected in a huge atrium that still impresses visitors today. Perhaps such extravagance can be seen as exemplary of the ideological confusion that characterised late-socialist East Germany.

Fittingly, one employee of Kajima, interpreter Seiichi Furuya, documented some of the last years of East German life with his (Japanese) camera before returning to Japan in 1987.

GDR-Japan relations developed in tandem with the disintegration of Comecon. In 1980, for example, in deliberate retaliation for a reduction in Soviet oil supplies, the GDR reneged on a promise to purchase a Soviet colour television factory and bought from Japan instead. The GDR borrowed heavily from Japanese institutions, which came to own over three quarters of its hard-currency debt. And, according to Der Spiegel, ‘KoKo’ (a sort of foreign-economic wing of the Stasi) arranged deals with Japanese pharmaceutical firms, offering East German citizens as guinea pigs.

Thanks Gareth, that’s really interesting (and quite scary) stuff. I was meant to write another post on the debt and trade issue in the 1980s. Have you got some statistics debt figures?