Reinier de Graaf of OMA wrote an article which beautifully builds bridges between architecture and Piketty’s theses on income inequalities. Time to reflect on some of this, almost exactly a year after I wrote my own review of the economist’s tome.

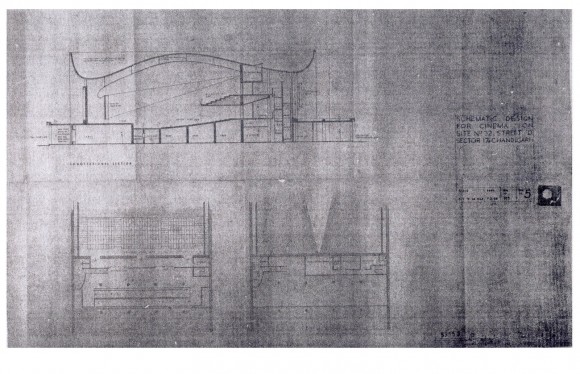

Neelam Cinema (Aditya Prakash), Chandigarh

Neelam Cinema (Aditya Prakash), Chandigarh

First off, de Graaf’s article is extremely worth the read, even if you’re neither a fan of architecture nor of economics. I haven’t seen much reaction to the piece other than on the Dutch online magazine Dafne. Therefore please excuse extensive paraphrasing and summarising, which is followed by my own thoughts towards the end of this longish post.

“Architecture is now a tool of capital, complicit in a purpose antithetical its social mission” (the piece’s title) sounds like a pamphlet from the outset, but is in fact a personal essay that tries to contextualise the architectural profession in the new “gilded age” that Piketty has proclaimed.

After a non-technical summary of the main tenets of Piketty’s book, de Graaf places his own biography at the tail end of the “emancipatory period”, the post-war era of redistribution, progressive social policies, and modern architecture with its utopian visions for the future:

From Le Corbusier to Ludwig Hilberseimer, from the Smithsons to Jaap Bakema: after reading Piketty, it becomes difficult to view the ideologies of Modern architecture as anything other than (the dream of) social mobility captured in concrete.

The aberration of the 20th century, during which capitalism’s inbuilt automatism of greater capital returns over economic growth often lay in reverse, began with the destruction of the First World War. At the same time, the Futurist Manifesto by Marinetti heralded “cultural rejuvenation and aggressive modernisation”.

Shuto Expressway, Tokyo, 1964

The European avant-garde took hold, and in its wake, novel forms of architecture and a new political and social awareness of the profession. From early on, progressiveness and revolutionary zeal were a double-edged sword. It meant that Le Corbusier could work for both Vichy France and Stalin’s USSR.

Fast forward to the 1970s, and the relationship between capital returns and economic growth has reversed. The conservative revolution sweeps through the US and parts of Europe. In 1972, the Pruitt-Igoe housing estate is demolished, heralding the beginning of the end of modern architecture and its utopian visions. In de Graaf’s words,…

…[t]he mood becomes pensive, the major seminal works of architecture are no longer plans but books, no longer visions but reflections. It is telling that the most noteworthy architectural manifesto of 1989, the year of the fall of the Berlin Wall (…) is A Vision of Britain by Prince Charles. The modern age prefigured in ‘The Futurist Manifesto’, at the tail end of the Ottocento with its hereditary hegemonies, ironically concludes with an anti-modern manifesto by a member of the British Royal Family.

He goes on to say that…

[i]f the egalitarian climate of the ’60s and ’70s had made modern architecture generally unpopular, the neoliberal policies of the ’80s and ’90s made it obsolete. The initiative to construct the city comes to reside increasingly with the private sector.

Housing associations are privatised and home ownership rises dramatically, famously under Margaret Thatcher’s “Right to Buy” in the UK. Hasn’t this made our societies much more conservative? After all, home owners are interested in low interest rates and low inflation. (My friends in the UK talk about buying their first house as is common everywhere. Will they automatically hate fiscal deficits as a result?)

This marriage of convenience between the right and home owners has worked fabulously well during an era of unprecedented asset price increases, one that saw house prices rise for several decades in a row. Low wage growth becomes socially acceptable if a broad enough middle class can enjoy returns on their assets, so the theory goes.

Woolwich Arsenal, London

But for our generation, this “Faustian pact”, as de Graaf calls it, presents the short end of the stick. Wage moderation and inflated house prices make home ownership a distant dream: Many of today’s first-time buyers earn too little, or have too little job security, as to put down the required deposits for a house or apartment with the same proportions compared to their parents’ generation.

We so desperately want to get on the housing ladder, but fail to understand its perverse (historical) mechanism.

This leads de Graaf to discuss the recent decade’s real estate narratives. From a means to provide shelter (and convey social visions), the built environment becomes “a means to generate financial returns”. You don’t use a building, you own it, and hope dearly that your underlying investment yields decent returns.

Captured by economists, architecture has become inexplicable to itself:

The logic of a building no longer primarily reflects its intended use but instead serves mostly to promote a ‘generic’ desirability in economic terms. Judgment of architecture is deferred to the market. The ‘architectural style’ of buildings no longer conveys an ideological choice but a commercial one: architecture is worth whatever others are willing to pay for it.

The means by which architecture was once made affordable (prefab, industrialised building, etc.) are now employed to make architecture “cheap” and increase the returns.

De Graaf continues with a little detour of the London real estate market, replete with anecdotes of the super rich. He concludes the article with a series of powerful statements, and I take the liberty to continue quoting him:

Fifteen years into the new millenium, it is as though the previous century never happened. The same architecture that once embodied social mobility in béton brut, now helps to prevent it. Despite ever higher rates of poverty and homelessness, large social housing estates are being demolished…

Perhaps Piketty’s theory, the final undoing of the 20th century, finds concrete proof in the methodic removal of its physical substance.

There is so much to reflect on in the above and in the article. If you have made it so far, you will probably not mind a few more thoughts on this subject.

As one of the biggest and most successful architectural practices worldwide, OMA/AMO obviously carries some clout. This gives de Graaf’s essay punch. At the same time, critics may point to OMA’s seeming complicity in serving the benefactors of the “gilded age”, such as Dasha Zhukova and Miuccia Prada.

Antilia, Mukesh Ambani’s residence in Mumbai

While Piketty has taken much heat between last year and today, his theses largely stand. A spreadsheet problem and the usual cacophony of reviews worthy of a book like this notwithstanding, a very biting criticism came from Matthew Rognlie, 26, recently, who questioned the assumption that capital returns will continue to exceed economic growth in the future.

Without going into too much detail here, this line of debate often omits that economic growth also appears to be caught in a secular decline. This is a result of the technological frontier we have reached. It is also imperative given the ecological constraints our planet is facing. And as long as there are countries eager to catch up, higher-yielding investments will exist. The ability of capitalism to generate returns amid low economic growth should also not be underestimated.

So without knowing exactly how the relationship between capital returns and economic growth will pan out in the future, there are grounds to believe that Piketty’s theorem r > g may continue to hold in the 21st century. And even if you don’t buy this, a ‘gilded age’ can also exist on the shoulders of huge wage inequalities alone.

All this carries huge implications for de Graaf’s piece: How will home ownership evolve and what political implications will this have? At the moment, asset prices are (artificially?) boosted by ultra loose monetary policy. Can house price appreciation detach itself from lower structural economic growth? Will asset price bubbles be an inevitable feature of our new economic normal and its structurally low interest rates?

Also, what role will fiscal spending have in a future of structurally lower growth and lower interest (hence borrowing) rates? Can the public sector be brought back into the fold, retaking control of the built environment? Or will fiscal retrenchment mean a further privatisation of the built environment and formerly public spaces?